Around two-and-a-half million years ago, just East of Hudson Bay in Canada, it began to snow. While snow in Canada is not particularly unusual, this snow didn’t melt in the Summer. At least, it didn’t melt as quickly as it fell during the Winter. As the snow built up over hundreds of years, it began to compress under it’s own weight. The bottom of the snow pack turned into a very dense form of ice which eventually began to flow outwards, a bit like pancake batter until it reached Southern New England.

The same process was simultaneously occurring in other parts of North America and Europe. Forty-Thousand years later, the Earth began to warm again. The ice melted and retreated. This cycle has repeated itself every forty-thousand, and more recently every hundred-thousand years. While much of the evidence has disappeared, glacial ice is thought to have covered Southern New England several times. Geologists call this period of glacial cycles the ‘Pleistocene’.

This cycle of advancing and retreating ice, cooler then warmer summers, is in large part due to astronomical cycles. The distance and angle of the Earth from the Sun causes more or less solar heat to reach the planet’s surface. Greenhouse gases, the position of the continents and ocean currents all play a role as well.

The most recent glaciation in North America, named the Wisconsonian glaciation, lasted from approximately 85,000 years ago until 11,000 years ago. The ice sheet covering New England, the Laurentide, was a mile thick near it’s center and became tapered and rounded at it’s edges, similar to the pancake-batter analogy mentioned earlier.

Glacial Advance and Glacial Maximum

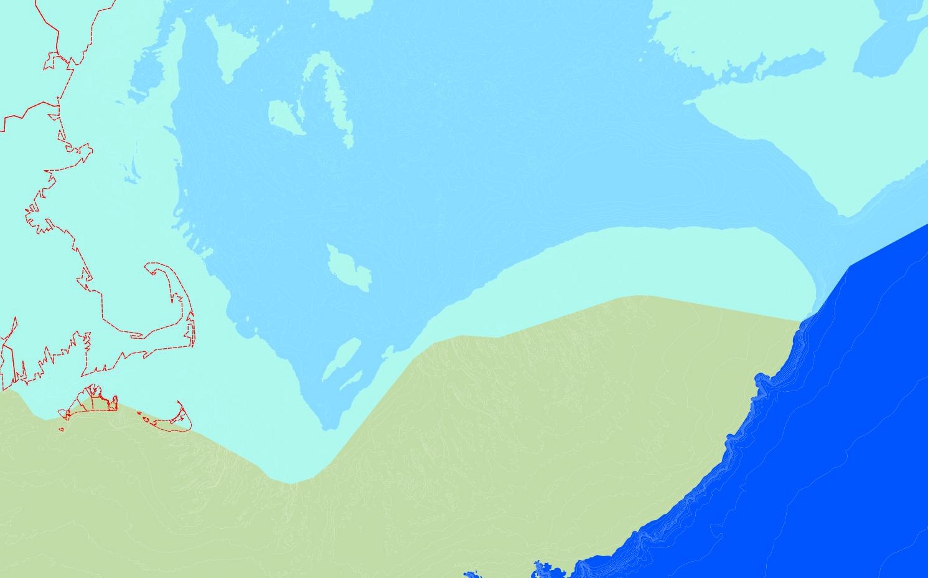

At the height of this glaciation, around 22,000 years ago, ice covered all of New England and extended south to Long Island, NY. Much of the Ocean’s water was taken up by the massive sheets of ice which caused sea level to fall by at least 400 feet. The shoreline was 60 miles east of it’s current location. George’s Bank, Stellwagen Bank and Jeffries Ledge were all connected to the mainland but were mostly covered by ice. (See Figure 1.) The ice sheet was up to 2 miles thick far inland but became thinner as it spread into lobes near it’s edge. On the North Shore, the ice was likely anywhere from 1/2 mile to 1 and a quarter miles thick.

Figure 1. Extent of Glacial Ice and position of the shoreline approximately 22,000 years ago. Current shoreline is displayed in red for reference.

Figure 1. Extent of Glacial Ice and position of the shoreline approximately 22,000 years ago. Current shoreline is displayed in red for reference.

Glacial Retreat

The advance of the ice halted around 22,000 years ago as the accumulation of new snow and ice near the sheet’s center reached an equilibrium with the melting of the ice near it’s edges. As the climate began to warm again, the sheet melted more quickly than it was expanding. This was not a smooth and continuous process but was marked by retreats, pauses and small advances only to retreat again. By 16,000 or 17,000 years ago the ice had melted North of Boston, at 15,000 years ago it was North of Cape Ann. A small re-advance of the ice occurred near 14,000 years ago and by 12,000 years ago all of Massachusetts was ice-free.

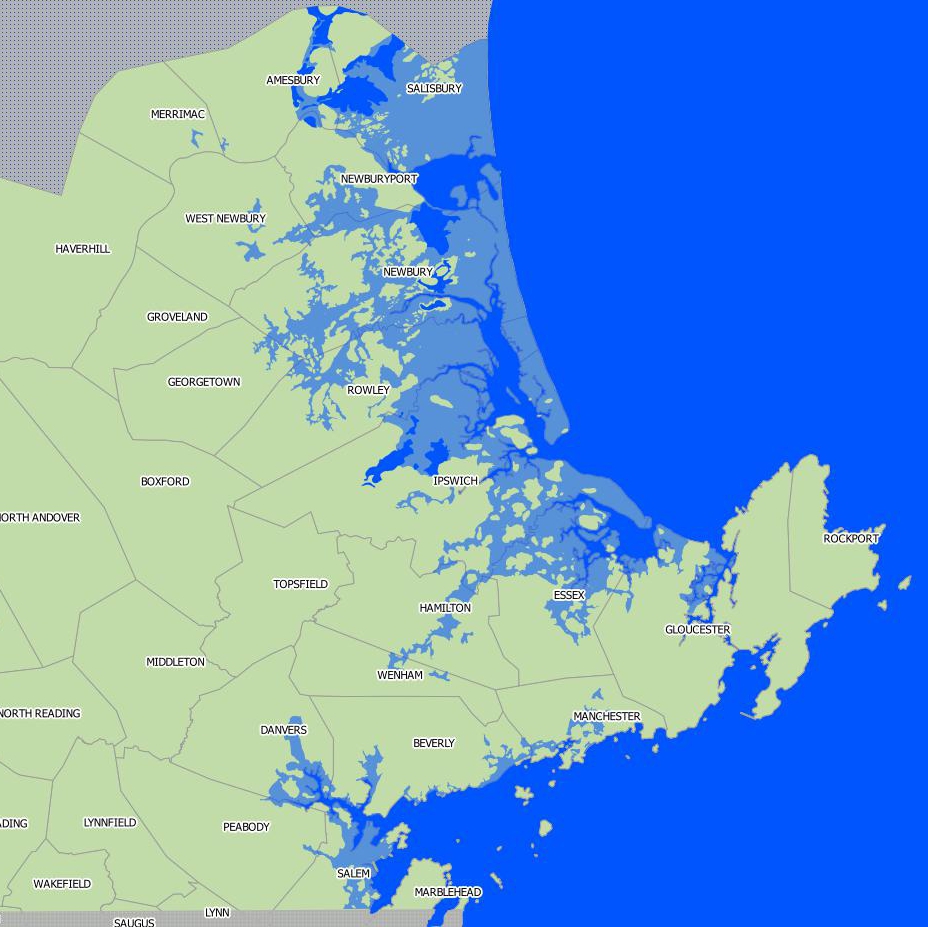

Figure 2.North Shore Shoreline 14,000 to 12,500 years ago. Lighter blue areas are submerged under water.

Figure 2.North Shore Shoreline 14,000 to 12,500 years ago. Lighter blue areas are submerged under water.

The sheer weight of the ice had caused the bedrock beneath New England to sink. As the ice sheet melted, water that had been trapped in the ice was released and sea-level rose 100 feet or so above current levels. The combination of these two events caused much of the North Shore to become flooded. 14,000 years ago, large portions of Salisbury, Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley, Ipswich and Essex were underwater. (See Figure 2) Evidence of this flooding can be seen in Marine Sediments far inland from the current shoreline.

At 12,000 years ago, the ice-free land slowly began to rebound upwards. Sea-level fell again to around 200 feet below current levels. The shoreline again receded and at this point, George’s Bank, Stellwagen Bank and Jeffries Ledge became islands. Similar to a rubber-band, the bedrock rebounded upwards, in some cases above it’s original level, and then again began to subside slightly. Ice continued to melt, raising sea-level again and these islands submerged underwater between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago. By 2,000 to 1,000 years ago the sea had reached it’s current levels and the shoreline looked very similar to what it is today.

Evidence of Glaciers on the North Shore

The North Shore of Massachusetts is literally covered with evidence from the Wisconsonian glaciation. The moving ice sheet and melt-water combined to erode and scrape away material from the landscape. Features on the landscape that were created in this way are called Erosional Landforms. The same action of ice and melt-water moved and deposited new material across much of the North Shore. These features are called Depositional Landforms.

Drumlins on the North Shore. Light Gray indicates areas where data is unavailable.

Drumlins on the North Shore. Light Gray indicates areas where data is unavailable.

Erosional Landforms on the North Shore

Glacial Plucking

Striations – Striations can be found everywhere but are marked on the Halibut Point (Rockport) trail map.

Removal of Bedrock and Soil

Depositional Landforms on the North Shore

Glacial Till – Glacial Till covers much of the North Shore

Drumlins – Holt Hill at the Ward Reservation in Andover and the Boston Harbor Islands are good examples.

Eskers – Many but Mass Audubon’s Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary in Topsfield has a large example.

Terminal Moraine – Dogtown in Gloucester has a good example.

Ground Moraine – Ground Moraine covers much of the North Shore

Kame Terrace – Julia Bird Reservation alongside the Ipswich River is one example. Many others.

Kettle Ponds – Horn Pond in Woburn, Pomps Pond, Pine Hole Bog and Berry Pond in Andover, Lake Quannapowitt in Wakefield among others.

Outwash Plain – Seine Field in Gloucester

Erratics – Glacial Erratics can be found in almost any conservation area on the North Shore.

Sources: